Today I’m diving into the first small shift you can make in your classroom to start implementing the Science of Reading research without feeling overwhelmed and all the other feelings that come with it. My goal is to help you make small shifts that create huge results in your classroom for how your students can read.

This blog is part of a series. If you missed the introduction, called Shame on You Teachers, please read that first to see where this is coming from. And don’t worry, “shame on you” is not what you think. So, start there and then come back here to read about the first shift I recommend making in your classroom.

Swap leveled books for decodable readers

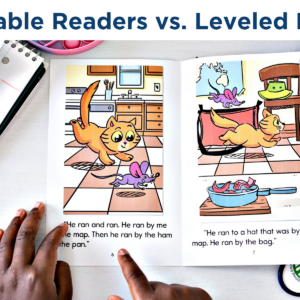

The first shift I would love for you to make if you have students reading on Level A-F(ish) is to use decodable readers instead of leveled books.

I use the “ish” because we know all children are different, so I hate being so finite with the levels. But overall, for the early readers, put the leveled books aside and use decodable readers instead.

Remember, this is a small change to keep you from feeling overwhelmed. I want these shifts to feel like baby steps until you’re ready to go full-in, but they will still reap huge results in the meantime.

Why use decodable readers?

Unfortunately, for some reason, balanced literacy has become synonymous with the three-cueing systems. While the system was part of balanced literacy, balanced literacy was so much more than that.

When students are reading a level A reader and come across the word “strawberry,” a child will not be able to read it. They don’t have the “code,” meaning they don’t understand all of the sounds in the English language. There are 44 sounds, and if students haven’t learned them all, they will not be able to decode the word “strawberry adequately.”

In the past, when students came to the word “strawberry,” we would move into the three cues. Here are the typical cues and how we will work on shifting them.

1. Let’s look at the picture.

Looking at the picture is where the “guessing” argument stems from. Students can look at the picture and see a strawberry. They didn’t look at or decode the word. This is where there is a lot of contention on the three-cueing system.

So, let’s take out this cue and switch it.

We’re going to shift from having students look at the picture to focusing on looking at the word. But we’re also not going to have students use leveled books with the word “strawberry” in it. Instead, we’re going to use decodable books.

Decodable means the student can sound out the word. They know the “code” (the codes are the 44 English sounds) to break down the words in the decodable book. In addition, decodable books spiral in skill. So we have them use a very specific scope and sequence to get through all 44 sounds in the English language.

2. What word would make sense in the sentence?

If a child came to a word in a leveled book that they didn’t know, sometimes our cue was to ask them what word would make sense in the sentence.

I never really hated this cue. It means we’re asking the child if they understand the context of the sentence. If they understand the context, they are contextual readers and comprehend what they’re reading.

So, I never hated that cue because being a contextual reader is important.

However, we don’t want them “guessing” what word makes sense in the sentence anymore. Instead, the research says we need to make them focus on the word. So, when they get to a word they don’t know in a decodable book, we’ll tell them to look at it and start sounding out and decoding the letters, or graphemes, in that word.

3. Look at the first letter of the word and get your mouth ready to start saying it.

This cue focuses on the beginning sound, which is good. But it doesn’t move on to reading through the other sounds. Instead, the cue was to start with the first sound, look at the picture, and guess what would make sense. So it was kind of using all three of the cues together.

So, we want to get rid of this cue.

Instead, we want to tell students to look at the word, get their mouths ready and say the first sound in the word. Then, we want them to go to the following letter and see what sound that letter makes. And then, go to the next letter to see what sound that letter makes.

This is how we want to cue or prompt our students when they come to words they don’t know. We want their eyes to stay on the word they are trying to read.

The science tells us that the three-cueing system is harmful to students, and I agree with that 95%. So, we’re going to change our prompts and have the students think about the sound each letter makes.

As students become more proficient in their reading, and you’re bringing in diagraphs, blends, trigraphs, and vowel teams, it becomes more complex. But before you bring in those more complex sounds and skills, we must be very explicit and systematic in introducing the sounds to students.

Get your FREE download

If you need a scope and sequence that’s explicit and systematic, and you don’t have one, I have one that you can download for free. You can click here and scroll down until you see “Structured Literacy with E.A.S.E Getting Started Guide.”

There is an incredible, systematic, and explicit scope and sequence that you can use in your classroom for free.

So, the first shift you can make in your classroom to implement the science is to swap leveled readers A-F with decodable books.

I’m all about small, incremental changes because I want you to buy into this in a way that doesn’t overwhelm you more than where you already are. Because we all know teachers are overwhelmed. My goal is to help you intentionally, methodically, and slowly implement the Science of Reading research, so you don’t feel overwhelmed.

Options for Decodable Readers

Options for Decodable Readers

You can do a few things if you don’t have decodable readers. First, there are tons of decodable readers online. You can find them anywhere. Second, I have created 300+ decodable and Structured Literacy with EASE. And I kept them as inexpensive as possible because my goal in life is to help teachers teach kids how to read and love reading. And I’ll stick by that forever.

If you need decodable books and your district isn’t going to buy anything you can use, check out Structured Literacy. You can have 300+ decodable readers at your disposal for a low price. If you want books you don’t have to print out, you can buy our Decodable Readers if you have school funds through a purchase order. We also have all of our Developing Decoders on Amazon.

So the first shift is to switch out leveled readers for decodable books. Keep in mind, though, leveled readers are not bad. They’re just books. But science tells us that the books we’re reading to beginning readers need to start with decodable readers, and I agree.

I haven’t always done that in my classroom, but we continue to “know better, do better” to move through the research and implement it. So, we will make small incremental changes together to implement the science without feeling overwhelmed.

How to use a decodable reader

How to use a decodable reader

Below, I will share how to use one of my decodable readers, Pat the Rat, in your classroom. You can also watch the demonstration on my YouTube channel here.

Pat the Rat uses the short a (ă) sound and words with the phonogram “at” throughout the story. I’ll break this down to show you how I would teach from this book. But first, we need to talk about high-frequency words.

Teaching high-frequency words

Children need a strong foundation of high-frequency words because they can’t read books, including decodable books, without some knowledge of them. So, we need to give students a foundation and bank of high-frequency words to read decodable books. However, we’re not going to build that bank through memorization.

Instead, we’re going to systematically and intentionally pull out high-frequency words to explicitly teach children the code to sound them out.

There is a list of 109 most used high-frequency words in children’s books. Only 33 of those words have an irregular part, which means the majority of those words are decodable. But students might not have the knowledge base of that specific phoneme or all of the 44 phonemes to decode the word. So, it’s our job to teach them.

Here is how I include this in my instruction.

“This is a home for Pat.”

The book’s first sentence is, “This is a home for Pat.” Many SoR advocates will claim this book isn’t decodable because the words “home” and “for” are on the page. But remember, we’ll help our students build a bank of high-frequency words through word mapping.

When reading this book with my students, I would have already explicitly taught them the word “this” as a high-frequency word through phoneme graphing. The word “home” is a CVCe word; however, it’s a regular word. And the word “for” is another high-frequency word.

When we get to the word “home,” I will use a Map-Its-Paddle and do the following:

- “Boys and girls, let’s look at the word instead of the picture. Let’s talk about what that word is. What’s the first letter? It’s an H. What sound does H make?”

- Write the letter H on the paddle while the students make the sound.

- “Okay, now we have the letter O here.”

- Write the letter O on the paddle. Then, write the letter M.

- “What sound does M make? /m/. Good. M makes the /m/ sound.

- Write the letter E on the paddle.

- “At the end of that word is the letter E. Boys and girls, we know H and M make the /h/ and /m/. Now, that letter O says (ō). Listen and watch me.” Sound out the letters H, O, and M, then say “home.”

- “You’re probably looking at the E because sometimes E makes an ‘eh’ sound. But in this word, the E is silent because of the Magic E rule, which you haven’t learned about yet, but you will.”

When we do this, we’re planting the seed for what is to come, and I’m okay with it. I believe a decodable book has to be 96-98% decodable to be considered a decodable book. So when you find a few words in the book for which students don’t know the code, you can work through them, as I showed you above.

It’s a quick and simple mini-lesson that plants the seed for what’s to come, and I believe that’s important.

Continuing on with the story

The second page is “Pat is a rat.” The students can do that sentence. They know the ‘A’ and have learned when the letter ‘a’ is in a sentence, we usually make the schwa sound. So again, it’s something I’ve already taught them.

The following two pages are “Pat is a fat rat.” and “Pat the fat rat sat.” The students can do all of that. Is it juicy and meaty? Not really, but we’ll get there eventually.

“He sat on the mat.” So we know Pat is the character, and we can talk about the setting and that he’s in a home.

Then we meet Matt. “Matt is a cat.” Then, he sees Pat. This part of the story is an excellent place to ask the students, “What do you think will happen in the story?” Asking questions is how you add rigor to a decodable reader.

You can say something like, “Oh boy, there’s a rat and a cat. What do you think’s going to happen?” Then, have students infer to help add in those comprehension skills.

“Pat ran from the cat.”

In our following sentence, “Pat ran from the cat.” we have “from,” which is another high-frequency word. It’s also an irregular word because the letter O makes the schwa sound.

This is another place where you can teach it in a foundation lesson before reading the book to introduce the word from and map it because it’s considered a heart word. Or, you can map the word with students while reading the story.

Write the word “from” on the paddle. The only hard part, or “heart” part, of the word, is the O. So, as you sound the letters out with the students, draw a heart under the letter O because it’s the only part they need to know by heart.

“Pat ran under a hat.”

The next sentence is, “Pat ran under a hat.” When students reach the word “under,” they may look at the picture. But we want to remind them to focus on the word.

Some SoR advocates would say this is not a decodable book because it doesn’t follow a specific scope and sequence. And I get it, but “under” is not irregular. It’s a harder word, but we need some of these words in decodables because we need to get some meat in our stories.

So, when we come to the word “under,” we’ll do some direct instruction instead of telling them to look at the picture. Here’s an example:

- “What do you think that first letter does? What sound does U make? Uh. Good, what’s the next letter?”

- “N. What sound does N make?”

- “Okay, what’s the next letter? D. What sound does D make?”

- “Good. So we have u-n-d. Then we have ER. Do you know what ER is? ER is bossy R and makes the sound ‘er’ sound. Can you say that? Er.”

- “So, we have u-n-d-er. Oh, it’s under.”

This is good teaching, in my opinion. While some SoR advocates will say it’s not a decodable book, I believe it is as long as 95-98% of it is decodable. Then, you’re planting seeds and teaching students how to attack words they don’t know.

That’s the goal

We want students to learn how to attack the word by looking at the word and not the picture. We want to teach them to start with the letters and sounds in the word.

Teach them. Plant the seeds for what’s to come. We want to expose them to words like these. We want them to master the code while exposing them a little at a time to words they haven’t learned the code for yet.

That is the first tiny little shift you can make in your instruction right now. Take out those leveled readers that are level A-F and use decodable readers. You can find them in our shop here or online in many places.

Remember, decodable books help students learn the code. Leveled readers are still good books. But we’ll not use them until students have mastered the code.

I have many more blog posts in this series that I can’t wait to share with you.

Thank you for reading, and I appreciate you being here!

Let’s make some slow changes to implement science in our reading instruction.